German Bakery and Sachsen Cafe

GERMAN BAKERY

Sachsen Café & Restaurant

The Bread Basket

History of Bread

The History of Bread dates back to the Stone Age, when people roasted the grains, or cooked them in water to make porridge. Once that mixture had the chance to dry completely, the result was a round, flat loaf which ultimately became bread as we know it today. In 500 BC bread was one of the major food staples in Egypt.

The Roman Goddess, Ceres, held in her hand the "ear of the corn" which was the symbol for agriculture. The name of the Greek Goddess, Demeter, also meant "mother of corn". By introducing additional recipes, the Greeks enabled people to purchase different varieties of bread. The upper classes used white wheat flour, which was considered to be more valuable than the dark flour used by the poor and slaves. That changed in the Middle Ages when aristocrats also enjoyed the darker varieties. The Romans were the first to bring bread into Northern Germany. In Middle European countries, bread was baked by monks until around 1000 AD when bakeries were opened. At that time, bakers shared one oven which was located in the town square, but eventually each baker had his own oven. Apprentices could be taught the trade only by bakers with a Master's Certification. In America, flat bread was made with corn until European explorers brought over wheat and rye flour.

The majority of the European bread is still made with sourdough, which is great for digestion, taste, aroma and shelf life as well. Dieter and Heidi, bakers in the 3rd generation, are still using the traditional recipes to this day.

The Roman Goddess, Ceres, held in her hand the "ear of the corn" which was the symbol for agriculture. The name of the Greek Goddess, Demeter, also meant "mother of corn". By introducing additional recipes, the Greeks enabled people to purchase different varieties of bread. The upper classes used white wheat flour, which was considered to be more valuable than the dark flour used by the poor and slaves. That changed in the Middle Ages when aristocrats also enjoyed the darker varieties. The Romans were the first to bring bread into Northern Germany. In Middle European countries, bread was baked by monks until around 1000 AD when bakeries were opened. At that time, bakers shared one oven which was located in the town square, but eventually each baker had his own oven. Apprentices could be taught the trade only by bakers with a Master's Certification. In America, flat bread was made with corn until European explorers brought over wheat and rye flour.

The majority of the European bread is still made with sourdough, which is great for digestion, taste, aroma and shelf life as well. Dieter and Heidi, bakers in the 3rd generation, are still using the traditional recipes to this day.

The Pretzel Saga

History tells us that Count Eberhard lost trust in his personal baker after he insulted and talked badly about him to other people in the village, and therefore he should have deserved the death sentence. The Count took pity on his baker because he greatly appreciated him for his dedication to the baking trade, and told him to bake a bread or cake within 3 days which should be better than anything he had ever eaten. It also had to be a baked good where the sun could shine through in three different ways. By accident the "Pretzel" got dipped into lye. Since he did not have the time to recreate his baked good once more, he baked it the way it was and sprinkled it with salt afterwards. At the end the count loved it and demanded more for the next day. The Pretzel thereby gave the baker his freedom and a second chance in life.

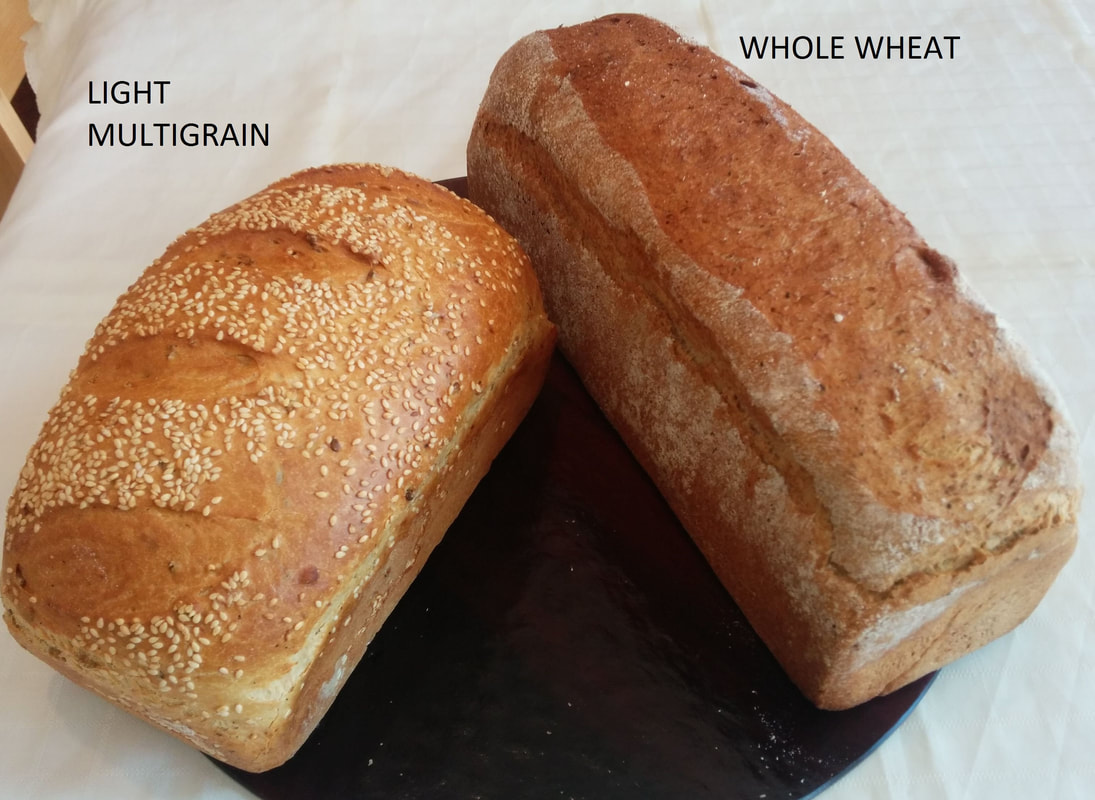

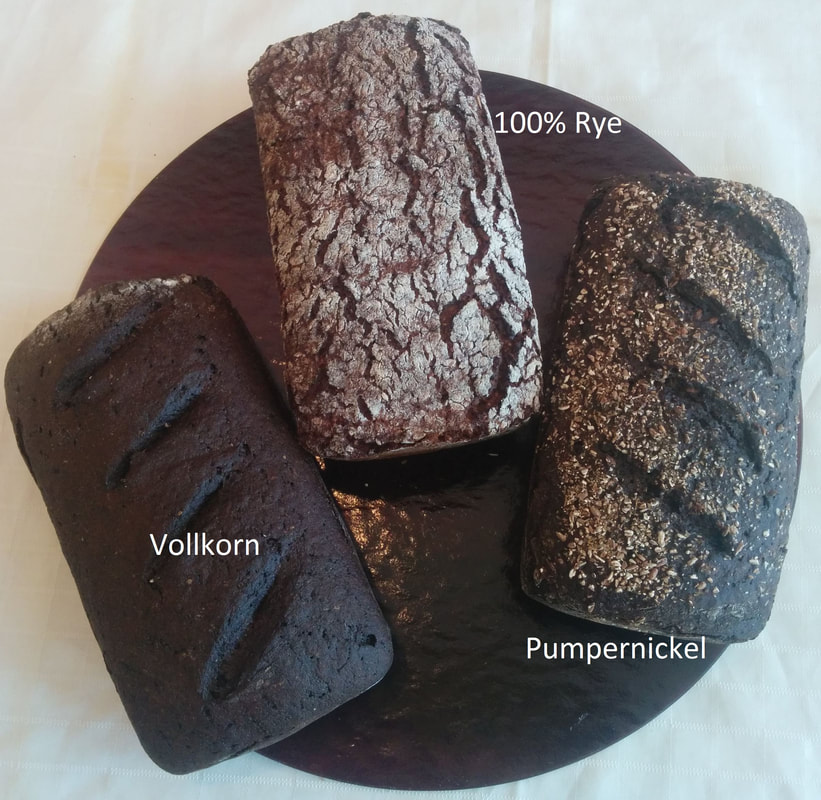

The German Bakery Assortment of Breads